There are hundreds of Unicorns already and an endless number of smaller ones, so which startup comes to mind is virtually impossible for me to guess.

But I bet you’re not thinking about the Bank of England.

When it opened in 1694, the Bank of England may have been the first startup in the world. You might be sceptical, but look here:

- Employees at the Bank worked in open-plan lobbies, so visitors and clients knew that transparency was part of the brand’s DNA.

- The Bank carefully designed a logo that would encourage trust in its consumers.

- It grew and evolved so fast, the government stopped being able to protect it. At one point, the Bank had to buy its own fire engines keep its archives safe — this was almost 100 years before London had its own fire brigade.

- The Bank also invested in state of the art technology: clocks. This might seem absurd to us today, but it allowed employees to be more efficient, stick to deadlines and an innovative two-shift workday.

Open plans, design thinking, explosive growth, cutting edge tech. Do you see what I mean?

The Bank of England, like many startups, faced another very modern problem. As it grew, it needed larger numbers of highly qualified workers with specific technical skills. But the English education system wasn’t producing enough of them. Historian and Dean at the University of Hertfordshire, Anne Murphy writes:

“Finding men with the right skills […] was a persistent problem” (please remember this happened during the 17th century — at that time, it was only men who the Bank employed).

Does this sound familiar to you?

If you are a founder, a recruiter or investor, it should. We have a severe shortage of tech talent in the ecosystem and as this demand continuously increases it keeps getting worse.

In the near future, this problem will affect a larger number of businesses outside of the tech community. The OECD, for example, predicts that 14% of jobs worldwide will be replaced by machines. The World Economic Forum points at even more alarming number: more than half of the global labour force will need to reinvent how they earn a living in the next five years.

These are mostly routine jobs with low-skill requirements in sectors like transportation, storage, manufacturing, wholesale, retail, and agriculture.

The good news is, according to a recent Deloitte study, for each job that disappears, around 4.4 new jobs will appear. These are likely to be high-skilled jobs requiring technical, analytical and creative capabilities.

Which is why the good news is also the bad news.

We won’t be able to transfer low-skilled workers from vanishing jobs to the new, extremely technical ones that appear in their place. It’s what Rainer Strack, leader of HR at the Boston Consulting Group, calls the “Big Skill Mismatch:”

Lucky for us, the Bank of England might hold the answer.

Faced with a shortage of skilled employees, the Bank of England started a program that hired thousands of employees with lower skills at entry level and trained them on the job. It produced a pool of workers with the exact set of skills that the Bank of England needed and an extremely reliable and loyal workforce.

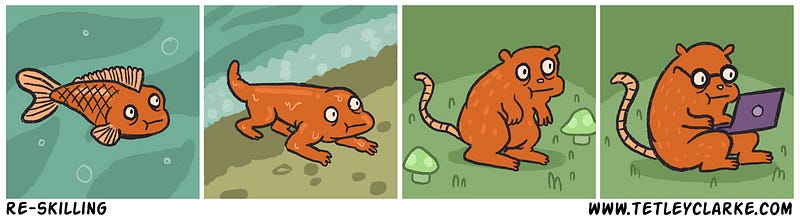

Today, this is called reskilling. And as business leaders, if we want to prevent a global workforce crisis, we have to implement it. We have to create a culture within our businesses where there is space for learning. Elizabeth Crowley, a policy and research professional at the CIPD suggests “putting learning and development opportunities right at the heart” of your organisation. Create programs and incentives. Give time and space. Make it constant and strategic, not just occasional. Award-winning journalist Nick Easen argues that if you don’t, “employees will go elsewhere.” I agree with him, I think so too. At the rate that technology is evolving, the jobscape is changing and global labour numbers are decreasing there really isn’t an alternative. We need to train new people and retain the old. We’ll either grow with our employees, or stagnate with them.

Next time you’re looking to hire, instead of spending 3 months hunting down that perfect 10x unicorn developer that codes in 16 programming languages, spend 3 weeks tracking down a few people who’ve taught themselves 1. Give them the time and resources to learn within your organisation — in the long term they’ll be much more valuable assets and loyal employees. And as they grow, so will your organisation.

This will be a big step towards solving the developing Workforce Crisis.

Pedro Oliveira

Co-founder at Landing

0 Comments